GOLDMINE #475

October 9, 1998

J.D. SOUTHER

He'd rather write songs for the likes of Brian Wilson, Linda Ronstadt and the Eagles than be in the superstar spotlight.

by Debbie Kruger

John David Souther is a wary man. For most of his 30-year career the Los Angeles-based songwriter and performer, whose musical compeers include Eagles, Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt, has resolutely shunned the spotlight his friends have basked in.

His wariness is almost amusing in light of the fact that his success has been variable and his treatment by the critics more often than not disdainful, but Souther takes himself extremely seriously and has no time for critics, anyway. As far as he is concerned, they don't get it.

|

|

His aversion to the media is met by an even greater disdain for over-zealous fans — he admits that he never smiled on his album covers because he did not want to encourage strangers to approach — and despite his low profile, or perhaps because of it, he has attracted his share of them. He doesn't want a bar of the website one devoted fan has painstakingly created for him, and is suspicious of people who spend time on-line — even while some of his friends and contemporaries such as David Crosby, Jimmy Webb and Andrew Gold communicate regularly with fans via the internet.

Publicists who have written overly flattering biographies in an attempt to hype Souther's achievements have been unceremoniously dispensed with. He doesn’t want to be hyped. He doesn’t want to sound exciting. “I want to sound like what I am – elusive and hard to find,” he says.

But find him, and catch him in the right mood, and Souther will wax eloquently about himself and his career for hours.

There are many paradoxes to J.D. Souther, a man who craves solitude and who has consciously — at times vehemently — resisted the constraints of a formal group situation, yet who is more likely to be remembered in the context of his working relationships with other artists. Critics have referred to him as a “marginal” artist, yet Souther has undoubtedly influenced his more commercially successful peers, his name popping up repeatedly in the stories of contemporaries such as Ronstadt and The Eagles.

In fact, Souther might have been a member of the Eagles, but chose not to be. His only group experience was in the 1970s with The Souther-Hillman-Furay Band, an experience he so despised that he forced its demise through his own hostility. “I’m not a great team player under those circumstances,” Souther admits, referring to then budding entrepreneur David Geffen’s plan for a country-rock “supergroup,” putting Souther, one of his original Asylum Records artists, together with Southern California music legends Chris Hillman and Richie Furay.

But the Eagles was another matter. Don Henley and Glenn Frey were his close friends; Souther and Frey had started out together in the folk-country duo Longbranch Pennywhistle which, in 1969, released one album of off-beat tunes for Amos Records that Souther now cringes at the recollection of. “We were new songwriters, and I didn’t have any illusions about writing the song of songs then,” he says.

Souther’s girlfriend at the time, Linda Ronstadt, needed a backing band, and he encouraged Frey to go on the road with her; that band became the Eagles. There were discussions about him joining the group — he even rehearsed with them. “But we were not essential to each other,” Souther says. “They didn’t need me in the band and I didn’t particularly want to be in a band.” Instead he helped write some their biggest hits, and despite their monumental success, he stayed detached. “I was a part of it in a way that suited us all best. I didn’t want to be answerable to four or five other people. I think democracy is a swell way to run a country, and not so swell a way to make art.” Life on the road wasn’t what he was after anyway. “I wanted to just stay home and write.”

Don Henley gushes about Souther’s talents, saying, “J.D. was the primary creative force behind Eagles songs such as ‘The Best of My Love’ and ‘New Kid In Town’.” Glenn Frey has said that Souther “gave away all his best songs. He would start things and we would finish them. When we would bog down we could always call him because he’s always been an inspiration.” Souther could probably live quite comfortably on royalties from Eagles albums alone, finding the 24 million-plus sales for The Eagles Greatest Hits album “very gratifying.”

In fact, Souther is one of the industry's more enduring songwriters, but he is less known than many of his songs. “Faithless Love” has been covered by more artists than Souther himself can recollect, from Ronstadt to Glen Campbell to Bernadette Peters. Ronstadt’s rock albums were laden with Souther’s poignant compositions, and his songs have also been recorded by the likes of Bonnie Raitt, Roy Orbison, James Taylor, Crosby Stills & Nash, Warren Zevon, Joe Cocker and Hugh Masekela — to name but a few.

With boxes of awards stowed away out of sight (“It’s just memorabilia you accumulate,” he says dismissively), Souther’s success has more often been measured through the artists who prospered from his craft, and this is despite a string of his own solo albums and a top ten hit, “You’re Only Lonely.”

The choice of an uncertain solo career over the high-flying Eagles option is telling. When Frey and Henley hit the road with Ronstadt, Souther began to grow his own wings. “In a way it was a big stepping stone for me as a writer, because then I really was alone, not part of a group any more. I was at home trying to figure out how to do this by myself.” He drew on the inspiration of his songwriting heroes — Tim Hardin, Bob Dylan, Hank Williams — whose work was deceptively simple. “It was such a step away from pop songwriting, where very often the most important thing to me sounded like it was just the rhyme, not the content. They really demonstrated the face that you could fill out your vision in a song without just rhyming words.”

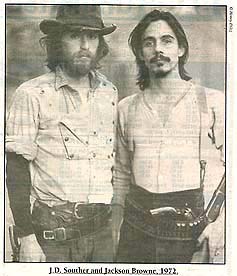

The young and earnest Jackson Browne, who lived in the same Los Angeles apartment building as Souther and Frey back then, was also influential. “I saw that there was something about that one-man kind of introspective songwriting that appealed to me, that was already in my nature,” Souther says.

Longevity was the goal. “I always thought, and I’m sure that Glenn and Don and Jackson thought too, that what we wanted to do was to write songs that would last, that that was more important than writing songs that were immediately popular. I wanted to write songs that would outlive me.” He admired Harold Arlen, the Gershwins and Cole Porter, and jazz was also a huge influence, although not an option vocally for the Detroit-born, Amarillo-raised Souther. “I love that music and in some way it informed the stuff that I did, but I just wasn’t good at it. I was like a folky, a guy with a kind of hick voice.”

Not too hick for him to be in constant demand as a session singer on hundreds of records by other people; Souther’s fragile yet feisty voice has graced the records of artists as diverse as Lowell George, Christopher Cross and Clannad.

Nor too hick to conceal the influence of another hero, fellow Texan Roy Orbison, whose dramatic falsetto resonates in many of Souther’s own vocal recordings. In 1988 Souther fulfilled a dream of performing with Orbison in the famed Black & White Night concert in Los Angeles. Directing the vocal arrangements, Souther assembled a backing chorus that included old friends Browne and Raitt, along with kd lang, Jennifer Warnes, Steven Soles and himself. It led to some writing sessions between Souther and Orbison with two of their collaborations appearing on Orbison’s final, posthumously-released album.

“I loved Roy when I was a little kid, I always wished I could sing like him,” recalls Souther. “He was like the Pavarotti of rockabilly music to me, although of course it’s not really rockabilly music, it’s really very operatic in a way.” Pavarotti is in fact Souther’s favourite vocalist, but one is less likely to hear that influence in his records.

While Souther’s eponymous debut album for Asylum Records was well received in 1972, it made little commercial impact. After two Souther-Hillman-Furay Band albums, he went solo again with the slicker Peter Asher-produced Black Rose, containing his own versions of songs such as “Faithless Love” and “Simple Man Simple Dream,” which received greater exposure from Ronstadt’s recordings of them. It was not until 1979, when the You’re Only Lonely album and its Orbison-inspired title track hit the charts, that Souther achieved the commercial success his old friends had been experiencing throughout the preceding decade. He says the limelight was great for a while, but ultimately the fame game felt wrong. “Some of it is just wretched because you feel like you’re being watched all the time. And I’m too self-conscious to want to be watched all the time. I can exude confidence but I don’t necessarily have it.”

Yet the supposedly self-conscious Souther has, in middle age, begun a career as an actor. While his musical friends were touring the world and trying to save it with benefit concerts, Souther stayed in Hollywood writing melancholy love songs and making friends in the film industry. After his fourth solo recording effort, Home By Dawn, went virtually unnoticed, he turned his hand to writing and recording songs for several film soundtracks, from Urban Cowboy to About Last Night..., and eventually the opportunity arose to step out of the studio and in front of a camera. In the late 1980s he was offered a small continuing role in the television series Thirtysomething, then a cameo as a singer in Steven Speilberg’s romantic fable Always and a small support role in Postcards From The Edge.

After a more sizeable part in the schmaltzy My Girl 2, Souther concentrated on a string of low-budget films that have never had cinematic release. At the unglamorous age of 52, he is humble enough to admit he is still on a big learning curve. “They’re not hiring me to be beautiful,” he states philosophically, his Clint Eastwood-like weathered cowboy looks leading to his being cast as Jesse James in Purgatory, a recently filmed movie for cable television network TNT.

The cowboy image is not that far-fetched. From the early 1970s, when Souther and Browne posed as outlaws along with the members of the Eagles on the back cover of that group’s Desperado album, this civilised hillbilly has never shrugged off the L.A. country-rock tag. His collection of cowboys boots is impressive but he doesn’t walk far in them. While Ronstadt quit L.A. many years ago for San Francisco and now Tucson, and Henley settled in Dallas, Souther has remained in the Hollywood Hills, yearning for a life less cluttered. A ranch in New Zealand is an appealing idea, but abandoning Los Angeles is an unlikely dream at the moment.

“I do like the idea of getting up in the morning and just getting on a horse and riding fence, instead of answering the phone...” his voice trails off as he contemplates the latest pressures awaiting him in his home studio. He has numerous projects on the boil, including collaborations with other songwriters which are often protracted, taking months to complete just one song. Late last year he wrote the lyrics to a Brian Wilson song for Wilson's album Imagination. For Souther it was the chance to work with an idol, The Beach Boys yet another early influence on him. “I heard ‘In My Room’ and some of those early songs when I was in Texas, and it was very much part of the painting of California.”

An opportunity also arose recently for Souther to write with Bob Dylan. “A mutual friend of ours had been trying to nudge us close together for years, and he finally came over one day and we sat and got almost nothing done. We talked about poetry and dogs.” Dylan’s inspiration is still a mainstay for Souther, who speaks reverently about his exalted language and important stories.

Don Henley is equally reverent about Souther. “He is a particularly well-read man and his linguistic skills have been extremely valuable. He is also gifted in the melodic area and has a mature grasp of phrasing — something that is sorely lacking in much of today’s ‘alternative’ music. He understands how particular notes and certain words coalesce into a phrase.” When Henley and Souther write together there are no holds barred. Says Henley, “We are old friends who have been through a lot together, which gives us a necessary lack of inhibition and an emotional empathy when we work together on a song,”

A song like "The Heart of the Matter" (from Henley's album The End of the Innocence) was written in the aftermath of broken relationships both he and Henley were getting over.

Henley has often commented on how he looked up to Souther when The Eagles started out, and 26 years and many collaborations later, little has changed. “When I’m working on a song, especially a ballad, and I get stuck for a lyric, I know I can always turn to J.D. and he will come up with something brilliant to fill in the gaps,” Henley says. “Or he will tell me frankly that the whole thing is garbage and I should throw it out and start over. I don’t always agree with his opinion but I respect it.” Henley's new solo album, due early next year, will, predictably, contain a handful of songs with Souther's songwriting credit.

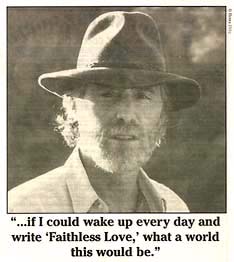

Souther is his own harshest critic, yet even impresses himself sometimes. “Unfortunately that doesn’t happen until time has added enough perspective to it for you to be truly surprised,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll hear something and just think, wow, I wish I could do that, and then I’ll realise, oh yeah, I did. It doesn’t make whatever’s going on currently any easier, though. I mean, if I could wake up every day and write ‘Faithless Love,’ what a world this would be.”

Does he have a favourite composition? “It probably just depends on the mood I’m in; it’s completely capricious whatever happens to strike me that day as having the most resonance. I was singing ‘Prisoner in Disguise’ once on stage and I almost began to cry, and it was kind of frightening actually, it had never happened in that song before. And from that point on that always had a little bit of extra sauce.

“Usually my favourite song of mine is ‘Simple Man Simple Dream.’ And it was written almost sarcastically. I mean the last thing I am is a simple man. It was more like what I aspired to be, some part of me.”

Souther is recording a new album of his own, but when it will materialise is an unknown. A self-confessed procrastinator, he prefers to submerge himself in the work of his friends; in addition to Henley's forthcoming album, Souther has co-written on the soon-to-be-released Joe Walsh album. But he has been mulling over his own next album for some time — one friend says it is around 10 years — putting down rough cuts for what is an eagerly anticipated release in many circles. Undoubtedly the Eagles’ resumption in 1994 renewed focus on other artists in that group’s immediate “family,” but for Souther, unlike The Eagles, there was never any “14-year vacation” — although it’s exactly that long since his last album came out.

“For me life just goes on in the same increments as it does for everyone else — seconds, minutes, days, weeks, months — so I can’t tell how people who haven’t heard any music of mine since 1984 are going to respond. Because I’m here every day, so I don’t have the luxury of those big jumps in perspective.

“But any artist is always going to tell you that they think the next piece of work they’re going to do is the best. So there’s no point not doing it.”

He accepts that things have changed since he started out, one of a band of merry musicians who seemed to only have to order a beer at the legendary Troubadour Club in Los Angeles to get a record deal. “The business is bigger, there are more artists, more singers, more writers, all that stuff has more commercial application than it had before. We were kids, you know. Everybody old was square and the whole world has since discovered four-chord songs and edgy rhythm. So it is harder to be surprised probably by anything.”

Moreover, Souther’s influences are less pressing. “I’m not in step with any music that’s being made right now that I hear,” he says, confessing that he misses the days when the likes of Ronstadt, Zevon, George and Raitt were all recording albums at around the same time, drawing off each other’s energies and talents. “This record is not being made in a vacuum, but rather sort of being made in a chaos of things I don’t find familiar or reassuring, because I don’t feel a part of anything that’s going on around me.”

Which could be why, in conversation, Souther talks about the past far more than about the present, why he rarely tours or performs live, and why he prefers the company of his dogs to people. In the 1970s one of the paradoxes of J.D. Souther was that the sensitive angst-ridden ballad writer was depicted by the press as “a rock & roll ass-hole who ate newsmen for breakfast.” Nowadays his bark is worse than his bite and he has mellowed.

|