|

|

APRAP

December 2002

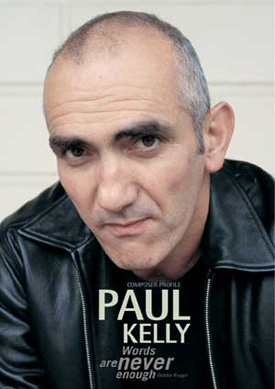

PAUL KELLY

WORDS ARE NEVER ENOUGH

COMPOSER PROFILE

Debbie Kruger

Paul Kelly is a man of few words. At least when it comes to talking about his songwriting he is. His songs overflow with lyrics that invite interpretation and analysis, his influences include great literary figures such as WB Yeats and Raymond Carver and his songs often carry literary references. He has published two books of lyrics and his website also contains lyrics to dozens of his songs. Words are everywhere – except in conversations about them.

|

Referred to variously as a poet, a political commentator, a storyteller, “a mirror to the Australian spirit,” Kelly sees himself largely as a music man. “There’s been an imbalance of focus on my words, because it’s a musical thing first,” he says. “The words always serve the music, generally. I hardly ever write a lyric and try and put music to it. I know some people do but it doesn’t come to me that way.

“Focus on the lyrics is fine, because I think lyrics are important, but often it’s at the expense of people focusing on the music. Which I think is just as important.”

With music his declared motivating force, Kelly has been enjoying his increasing forays into screen composing, his most recent successes the collaborative efforts on the Lantana score and the soundtrack to One Night the Moon, the latter winning him an award for Best Soundtrack at the APRAAGSC Screen Music Awards last month.

But it’s his large and outstanding catalogue of songs for which he is best known and revered. There are so many that sometimes he forgets what he’s written. Nevertheless he remembers his first song, written at the age of 19. “I was listening to a lot of Astral Weeks at the time, so it was sort of Van Morrison,” he recalls. “It was called ‘It’s the Falling Apart That Makes You’, something like that. I remember it. It was an open tuning.”

Before taking up guitar at the age of 18, Kelly had studied trumpet and piano at school. He was also writing poetry, but qualifies: “Everyone writes poetry when they’re 15 or 16.”

Kelly’s poetry most often rhymed, as do his song lyrics. Given that his songs are so wordy, that’s a lot of rhyming to accomplish. “I’m a bit of a rhymer, but one of my favourite songwriters, Iggy Pop, is a great example of a songwriter who writes fairly standard sort of versechorus things but often doesn’t worry about the rhyme. I like rough rhymes. I tend to use rough rhymes a lot, because it feels more natural. Things are rhyming but they’re not sounding too carefully rhymed, and that helps songs sound more conversational. But yeah, I have a natural tendency to rhyme. Even when I write letters to people I might rhyme in it.”

Starting a song comes easily to Kelly, melodies come quite naturally. But those much admired lyrics are more difficult. “I’ve got lots of opening lines, it’s getting the rest of the song that’s the hard part,” he says. “The third verse is usually the hardest. Often I have songs which I know the musical structure of it, I know where it should rise and fall in certain ways, and I’ve got most of the lyrics, and it’s just getting the last few final lyrics, that’s usually the slowest part.”

In some cases, a melody will be written years before Kelly finds lyrics to match. “Pretty Place” on his latest album, Nothing But A Dream, “was a really old one but the words came out fairly recently.” The writing of his classic “To Her Door” spanned a seven-year period. “I sing little melodies into a tape recorder and every now and then I go through the tapes and have a listen. And I heard that and I thought it would be good to put words to that, it’s a good tune.”

He says that – “it’s a good tune” – in almost throwaway fashion. “To Her Door” is one of his most popular songs, and featured in APRA’s 75th Anniversary list of 30 Best Australian Songs. Other classics, such as “Darling It Hurts,” “Dumb Things,” “Sweet Guy” and “Careless” are as recognized for their memorable pop melodies as for their lyrics. Over the past decade there has been a gradual shift as the writing has become more rhythm-based.

“I think for a lot of songwriters it’s a fairly natural evolution. When you first start off you probably have your own thing that you do and then you get sick of your own template, I guess, and you want to find other ways to write. So I’ve done it more over the last five or six years where I write with a band and the way to write with a band is that you don’t start with a melody, you start with a groove or a fairly simple chord structure and then you write over the top of the rhythm. I’ve always tended to do that with my bands, even with the Coloured Girls and the Messengers, we would sometimes get songs just by playing with the band. I always wanted to write that way. I’ve done it more recently because the musicians I’m playing with are quite versatile and have had strong funk, soul and reggae roots. So we can just play around and start trying to write things over the top of it.

“I think it’s a natural tendency of any writer to try and find new ways to write. No matter how wide-ranging your influences, we tend to fall into our own patterns. They’ll always keep coming back; some songs I write now sound like songs I would have written 20 years ago, but there are other songs I write now that I could never have written then.”

Kelly admits to having many unfinished songs. He is rarely so attached that he will persevere relentlessly. “I’m usually thinking of more than one song at a time, so it’s like – this is not working so I’ll scratch around with that one. I have more music than I have lyrics, so there’s always a pile of song ideas there, and if I’m not getting anywhere with one song I just have a crack at something else.”

He is also comfortable following the subconscious directions of a song rather than trying to consciously guide the meaning. “I don’t start off with a very clear idea in my mind of what the song is going to do, so it kind of follows what words rhyme, other things that come into it. It’s a matter of having very light reigns.”

But there are songs that have specific intent – the ones for which he is known as “political commentator.” Songs such as “From Little Things Big Things Grow,” which he wrote with Kev Carmody about Aboriginal Land Rights, “Treaty” with Yothu Yindi on Land Rights and Reconciliation and “Little Kings,” from a more recent album Words and Music, about dissatisfaction with the Government. “Those songs are the exceptions,” Kelly concedes. “’Special Treatment’ is another one like that, a specific situation and write to it.”

Kelly has almost certainly co-written with more songwriters in Australia than anyone else. In addition to Carmody and the members of Yothu Yindi, he has also been drawn to work with indigenous artists such as Archie Roach, Ruby Hunter and Christine Anu. The list of female songwriters whose work also bears his name is extensive – Vika and Linda Bull, Renee Geyer, Jenny Morris, Deborah Conway, Wendy Matthews, Debra Byrne, Monique Brumby, Kate Ceberano, and more. And many other legendary Australian songwriters have chosen to collaborate with Kelly, including Nick Cave, Tim Finn, Ross Wilson, Garth Porter, Colin Hay, Joe Camilleri, Peter Garrett and Mark Seymour. And then there are his current band members, among them Shane O’Mara, Stephen Hadley and Peter Luscombe.

“You often write songs with collaborators that you would never write by yourself,” Kelly explains. “It’s a way of dragging a song out of you that you wouldn’t have come up with.”

Kelly has always eschewed the label of “storyteller,” and insists that his songs are not autobiographical. The pictures he paints in music and words are just that – pictures. “A lot of my songs are very situational; they come from imagining someone in a particular situation. Sometimes a sequence of events happens which makes it more a story, but other times it’s just that situation. I guess most music theatre writes from that point of view.”

While Greg Macainsh’s evocative songs for Skyhooks were not a direct influence – he cites The Triffids, Go-Betweens, Hoodoo Gurus and The Saints as having a strong effect – Kelly acknowledges that songs like ”Carlton” and “Balwyn Calling” suggested a sense of urban place which Australian pop had not done previously. “From St Kilda to Kings Cross” is the most blatant of Kelly’s evocative pieces, but nearly all his songs are full of pictures of lives going on in Australian cities, parks, houses, jails.

“I’m sure that I was aware that what Skyhooks were doing was writing about places around them. Like Chuck Berry – I loved his songwriting, it had very specific details in them, they were songs you could see as well as hear; they were very cinematic. Lou Reed’s a very cinematic songwriter, too.”

Kelly’s attraction to the theatrical, however unconscious, has meant occasionally a song’s character will pop up again, sometimes unintentionally. “I’m sort of aware where certain songs are written a few years apart from each other – ‘To Her Door,’ then ‘Love Never Runs on Time’ and ‘How To Make Gravy’ – I’ve got a feeling it’s the same guy. He keeps coming back.”

Maybe he’ll be in a happier place next time? “Yeah, he’s a bit of a fuck-up, that guy,” Kelly laughs.

Kelly’s work in screen music, from songs contributed to ABC TV’s Seven Deadly Sins series through the play Funeral and Circuses to his more recent music for Lantana and his pivotal role as songwriter and actor in One Night The Moon, which is operatic in presentation if not musical content, has regularly fuelled his desire to work in musical theatre. “I love musicals, I like opera, my grandparents sang opera,” he says. “It’s one of those things at the back of my mind that would be good to do. Probably where it hasn’t matched is that the kind of songs and music that I write don’t really suit music theatre voices.”

A libretto alone would not appeal, in spite of the potency of his lyric writing. “It’s hard for me to write words without music in my head.”

So back to the music. Early influences were varied. Bob Dylan was an obvious one, although obvious more in a lyrical way. Hank Williams, the Stanley Brothers, Muddy Waters and Howlin Wolf were musicians Kelly admired. “Folk, blues, country music and lots of hillbilly music,” Kelly says, admitting that Top 40 also played a part in his musical upbringing. “You’d listen to something and try to figure it out, get the chords.”

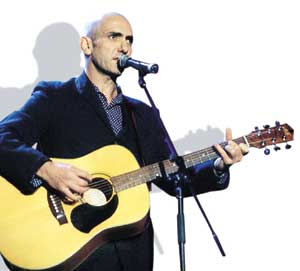

He says he does not hear melodies spontaneously when he goes about his daily life. He is a songwriter whose songs start when he is at his piano or strumming his guitar. He doesn’t write on the road. “I tend to write more songs at home when I set time aside.”

His songs are regularly covered, interestingly most often by women, yet Kelly sees himself primarily as a performer of his own work, and a performer only because he had written songs that he wanted to sing. He has occasionally recorded and performed covers of other writers’ songs – from the traditional folk song “Streets of Forbes” to Errol Brown’s Hot Chocolate disco hit “It Started With A Kiss” (which in Kelly’s hands sounds like it was always a gentle folk/pop song) – but doubts he would want to continue performing if he couldn’t write any more.

So between his own recordings and all those covers, there is a huge amount of Paul Kelly music out there. But ask him if he is satisfied with his body of work and the response is an immediate “No.” There is no resting on his laurels, despite 20 years of acclaim and popularity.

“I’m a writer, so I feel useless unless I’m writing. If a carpenter broke his hand or had an injury and couldn’t work, he wouldn’t be satisfied. So it’s the same thing; you’ve got to be able to do new things. Happiness comes from feeling useful.”

As difficult as it is for Kelly to talk at any length about his songwriting – especially those lyrics – so too is it tough to explain the magic of writing – how songs are written, where they come from. “John Updike said a great thing about writing, he said often you might just have two different sentences on a page, completely unconnected, and if you look at them long enough you manage to connect them up. So often songwriting’s a bit like that, when you’ve got a line here and a phrase there, and a vague idea there. Or you might have three or four lines that you think belong to different songs and they end up in the one song. It’s very mundane and it’s very mysterious at the same time. Often it’s just things people say. I guess a lot of my songs come from just what people say.

“A song is like something that you catch, so it feels like something that’s outside of you. It’s like catching a fish. The way Robert Hughes writes about a fish at the end of the line, you’re connecting to a whole other source. That’s the great feeling about it, that’s the big charge.”

Literary references again, from the wordsmith whose music is his muse.

Photos by Ben Saunders and Tony Mott

© APRA

|

|